How different cultures give feedback

Thinking about how our cultures might encourage—or hold us back from—soliciting feedback

I’ve been reading The Culture Map over the last few days, and I can really see why so many people have recommended it to me.

Based on surveys and hundreds of interviews with international business leaders, Erin Meyer’s The Culture Map aims to help people better communicate across cultures by mapping how various cultures communicate and relate to one another in a business setting.

(I encourage you to pick up a copy of the book to understand the methodology behind the research and findings. After reading the book, I now understand that those of you in, say, Germany, would appreciate an extensive discussion of methodology before diving in to examples, whereas my fellow Americans are probably chomping at the bit for me to get to the point already. If you’d prefer to understand the full methodology first, I encourage you to read the introduction of the book before reading this issue.)

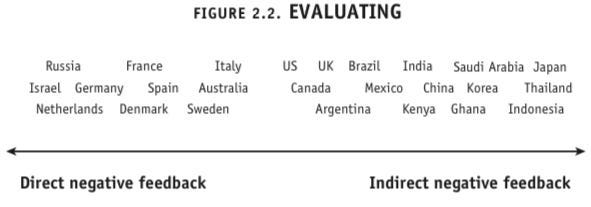

One chapter I keep turning over in my head in particular is the one on feedback, and how different cultures give one another feedback in a business setting.

She cites several examples:

A Dutch man giving his long-time colleague direct negative feedback in a meeting

Americans doing the “feedback sandwich” and starting with three positive pieces of feedback before mentioning something negative (even if the negative strongly outweighs the positive) — which then confused a French woman working in America, who was used to a French standard of mostly negative feedback with rare positive feedback

Brits holding an entire meeting and mentioning the negative feedback as an “oh by the way” at the end, with downplaying language (“This section could use a little bit of work” = it’s a complete disaster)…even if it was the point of the meeting

A Russian person berating someone perceived as subordinate in another department over the phone

A Japanese business person only giving feedback on positive elements of a proposal and omitting negative feedback on other elements, which the (Japanese) recipient knows to interpret as negative feedback

There are a few questions I find myself chewing on.

The first is on the beauty of the method of interviewing to uncover process. Having someone describe the process they’re going through to use your product or service and what their goals are — whether it’s paying invoices or team leadership transformation — does not necessarily require they say whether your product is good or bad. Indeed, we intentionally avoid that kind of question, as it usually does not lead to useful results. In asking about process and understanding where the frustrations are, those sorts of frustrations can come out naturally, without the person running into cultural norms around feedback.

It also makes me think about the magic of the “reaching for the door” question, which is where I find the real feedback tends to come out. It effectively fakes the end of the interview. I wonder if this is perhaps because it circumvents the cultural feedback patterns someone might have — a French person may have gotten their negative feedback out of the way in the beginning and then feel like they’re allowed to be more positive, or a British person may have buried the negative feedback until what they thought was the end, and after they’ve gone through that exercise in their initial response to the reaching for the door question, can finally open up about how they really feel.

And I wonder, what does this scale looks like for positive feedback? Meyer mentions how the French and Russians might be reticent to give positive feedback, yet we are not presented with a scale in the book. Americans, by contrast, will start with positive feedback even when it might not be entirely warranted, which makes other cultures perceive all positive American feedback as insincere because it’s delivered so often.

In a product design context, this sort of question matters.

For example, if you run a reviews website like TripAdvisor or TrustPilot, it would be relevant to know if the cultures your product is present in feel more comfortable giving negative or positive feedback. If it’s a culture where negative feedback is less socially acceptable, giving such feedback anonymously might be preferred, versus people in a direct negative feedback culture might be fine with their name and picture being associated with their review.

Are customers your superiors, inferiors, or equals?

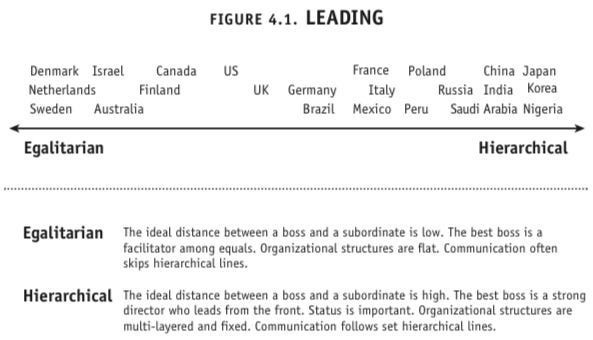

The curiosity I find myself coming back to the most is on the interplay of hierarchy and evaluation. There’s a whole chapter on hierarchy, and hierarchy also comes up briefly in various anecdotes in the chapter on evaluation.

For example, she cites a Chinese businessman who gives direct and harsh feedback to a subordinate in public. To give harsh feedback in public in the US, by contrast, would be an extreme breach of professional etiquette and reflect poorly on the giver.

She also mentions a Russian manager who was harsh and direct with a coworker in a different department that they had no previous relationship with, and in the chapter on hierarchy, describes Russia as a hierarchical system where one would be deferential to someone placed above themselves.

This makes me think about the fears people have about soliciting feedback from customers, and whether customers are perceived as superiors, inferiors, or equals.

For example, someone who comes from a hierarchical culture where customers are perceived as superiors and favors a direct negative feedback style might be justifiably terrified of getting feedback, as they’re effectively asking to be yelled at.

The US is less hierarchical than, say, Japan or France, yet more hierarchical than Denmark, where I live now. I’m thinking back to how I describe tone of voice during an interview as being “almost deferential:” this, I now realize, reflects my own cultural background coming from America, the land of “the customer is always right.” It isn’t a dramatic difference, yet one might say that in American business context, customers and clients are slightly above product/service providers in terms of rank.

In the book, I included an anecdotes about interviewing in Germany and Japan, which are further to the hierarchical side. In such cultures, even more deferential language is necessary, for example by using formal “you” pronouns or different grammatical structures.

Similar attitudes towards customer service don’t seem to exist in egalitarian Denmark, where everyone is perceived as equal and it would be socially unacceptable to view yourself as better than anyone else. You are rarely greeted when you walk into a store, and getting someone to email you back when want to pay them for something can be a challenge. (We’ve learned you often have to follow up on emails with a call, perhaps several times, which feels a bit aggressive by American standards.) It’s also a small country that prioritizes ties and harmony between people. Denmark is on the “direct feedback” side of the spectrum, yet less direct than the Netherlands. Negative feedback is given, but passively and wrapped in deferentially-polite speech—perhaps because it’s likely you’ll bump into that person again.

I wonder, does this make people more comfortable soliciting feedback? People know feedback will be given honestly when it is due, yet it will be carefully wrapped in a blanket.

It goes without saying that this research applies to business culture and not to personal life culture, which can be quite different. While it is based on research, it’s also generalizations (she describes the placement of each country on each spectrum as the center point of the bell curve for that country’s results). If you’re reading this and saying ‘this is just a bunch of generalized hogwash,’ please go read Meyer’s book. She does a better job explaining her methodology than I could. I recognize that there are differences between individual people, regions, and social contexts, as does Meyer.

Therefore Meyer, and I, present this research less as a rule and more so as a launching point for discussion and thought.

A couple questions for you

I’m now really curious about how you think about this, and I have a couple of questions that I’m hoping you humor me in replying to.

These are all questions I’m turning over in my own head, and I’m wondering about other people’s experiences.

I’m curious to hear about your own experiences with the interplay of hierarchy and feedback and whether you think it impacts your own enthusiasm or reticence to talk to customers.

Specifically, though feel free to take this in whatever direction strikes you:

What country and region within that country are you from? Where do you live now?

Would you say customers/clients are superiors, equals, or inferiors in your country? What leads you to say that?

For those of you who have interviewed customers, have you noticed differences in how people from different countries give you feedback, both positive and negative?

What else do you think I should know?

I moved from the US to the Netherlands less than 3 months ago. All of these points ring true in my experience. The "Dutch Directness" as its colloquially referred to, is similar to the outspoken nature of Americans but with no mention of the shit sandwich. They are happy to tell you how they feel about any topic and leave it at that. No need to go back and forth and come to a consensus unless the situation requires it.

One thing that has surprised me is the transparency present in TrustPilot scores. I work for an eCommerce company that prides itself on a roughly 4.2⭐️ rating. In the US, I would expect a lot of effort to be spent getting that number up to 4.75+. But the Dutch view feedback differently. If customers are more likely to tell you when things are going poorly, it makes sense to expect a lower average score. In the US, we've both seen the product reviews on Amazon that say, "Fast shipping, but doesn't really work right, but it looks nice. 3/5".

The product doesn't work and you gave it a 3?!?! That dynamic doesn't exist here. On the other hand, we have some contract employees in an East Asian country with a wildly different view of hierarchy. It can be tough to switch your mode of thinking to be empathetic and effective when communicating critical feedback around performance and expectations.

Here is another book about this subject written by a friend of mine. It was a good read as we were considering immigrating away from the US. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/13577633-subtle-differences-big-faux-pas

This is an infinitely fascinating topic, and something that I'm struggling with now having moved from New Zealand to Germany this year.

While not represented in this book, I'd say that New Zealand takes a lot of the best and worst things from Australian (quite non-hierarchical imo, to the point that could be considered disrespectful to other cultures haha) and UK (painful beating around the bush) culture - then add that same Danish dimension of relatively few degrees of separation.

In NZ, we definitely take hospitality and customer care fairly seriously. Service workers are baseline expected to be friendly, helpful, even to go out of their way a little to make you feel welcome (especially in a nicer establishment). There are obviously exceptions to this, but I think the rule generally holds.

This is categorically not my experience in Germany (at least, in Berlin). I've found the customer service baseline here to be...extremely MVP. Generally, you'll get what you need, but it's unlikely to be with a smile. That's fine by me! The points we really struggle with is when service is just... obtuse to the point you're not even sure this business really wants your custom. If you don't know exactly what you want, and how to ask for it, you are unlikely to get it. (You might even be blamed for not knowing :') )

For me, I think this is a big shift from being seen as a superior as a customer in NZ, to being seen as an equal here - plus a very high expectation for directness that's not so comfortable for Kiwis.

I haven't interviewed anyone here as I'm working remotely primarily with people in the UK, but it's been really interested seeing how this difference in cultures plays out with some of our clients from different EU countries as we start to expand.