If you find — or used to, before you read Deploy Empathy — the idea of talking to customers scary or overwhelming, there’s probably a good chance that wasn’t only with existing customers, but also with prospects.

And that’s completely normal.

For many founders, especially those who come from a technical background, sales settings bring about anxiety and nerves. You’re trying to show off your product, pray they don’t ask about anything that brings up deficiencies, and hope they buy. I’ve had founders describe it to me as peacocking since you’re trying to impress them. It’s a lot of pressure.

And the stereotypical image of a sales person doesn’t really help. For those of us who didn’t come into this world with a Patagonia vest and starched dress shirt pre-installed, it can feel like force-fitting yourself into a mode that just doesn’t quite fit. And that only makes sales even more uncomfortable.

Perhaps you dislike being sold to yourself, and hate when you have to talk to a sales person rather than being able to just buy a product yourself. That feeling only reinforces your own discomfort with putting on a peacock costume in order to make a sale.

But the good news is, you don’t have to dress like this guy in order to be good at sales.

Instead, you can use customer interview skills to build rapport, figure out which parts of your product are the most relevant to them, and have a low-pressure conversation to see if your product is a fit for their needs.

Getting those eating-some-ice-cream feelings flowing

One of the most important things you can do with a prospect is build rapport.

A typical piece of advice you may have heard is to find things you have in common: perhaps you went to the same university, know the same people, or have connections to the same areas.

But if you don’t have a degree, come from different places, and came in contact with this person cold (whether through your own outreach or inbound), you might feel a bit dispirited after coming across that advice.

So, forget it.

I’d argue that one of the strongest ways for building rapport with a prospect is the exact same way that you build rapport with a customer in an interview: by asking them about what they’re trying to do and listening to them, rather than trying to relate to them.

The “How to Talk So People Will Talk” chapters are the most important part of Deploy Empathy because they teach you how to build rapport and get someone to open up to you. And those skills can be used not only in customer interviews but in sales, negotiations, and so much more—even with friends and family.

I mentioned this earlier in the book, but the reason why this works is biochemical. Let’s take a brief detour to look at some scientific research on the brain when we talk about ourselves, shall we?

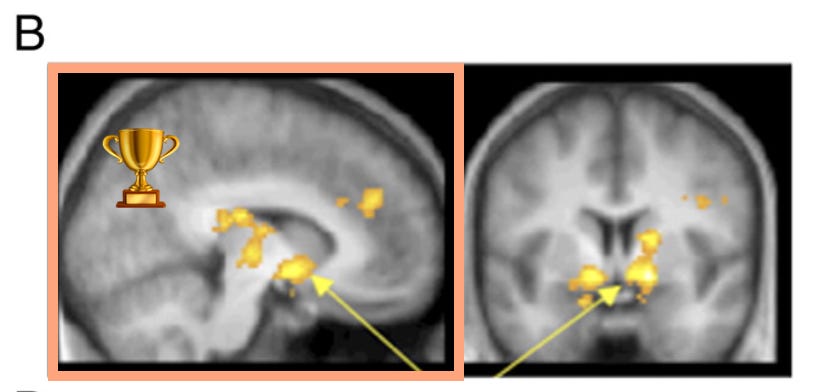

This is your brain on talking about yourself—even if no one is around to listen. Parts of the brain associated with motivation, pleasure and reward light up:

And when someone else is listening, the effect is even greater:

In other words, talking about yourself and your own experiences to someone else is like eating ice cream. As Scientific American put it:

Answering questions about the self always resulted in greater activation of neural regions associated with motivation and reward than answering questions about others, and answering questions publicly always resulted in greater activation of these areas than answering questions privately. Importantly, these effects were additive; both talking about the self and talking to someone else were associated with reward, and doing both produced greater activation in reward-related neural regions than doing either separately.

If you can get that eating-some-ice-cream feeling going in someone’s brain, you’re well on your way to having a good sales call.

And none of that requires being salesy. You don’t need a dialed-in elevator pitch, a perfectly-designed deck with a practiced script for each slide, or to practice in front of a mirror with your chest puffed out talking about how great your product is.

You can simply talk to them as a normal human being and listen to them. And they’ll find that very enjoyable.

Structuring your questions—and your eventual pitch—using Jobs to be Done

Yet the listening isn’t only for the purpose of building rapport: you can also use it to collect information about what they’re trying to do, why their current solution isn’t working, and whether your product might be able to help.

In the sales world, these approaches are known as “sales discovery” and “gap selling.” Sales discovery is an open-ended conversation to see if they’d be a good fit, and gap selling involves figuring out where they are now, where they want to be, and selling to the gap.

I say that partly so that you know that I’m aware that I’m not proposing anything particularly new or novel in terms of tactics here.

Instead, what I’m suggesting is that shifting your mindset to how you approach it, by borrowing from a setting that’s perhaps a bit more relaxed, could make sales less stressful.

And that environment to borrow from is—you guessed it—customer interviews.

You can use sales frameworks, yet you can also approach sales with a Jobs to be Done mindset. You might find it easier sketch out a basic Job Map or Buyer’s Journey on paper or in in the back of your mind as you ask questions and listen, rather than a sales-native framework. And crucially, asking Jobs to be Done questions will help you identify specific areas where they have pain points, allowing you to highlight those areas of your product. It becomes a problem-solving conversation rather than a sales pitch. (Again, nothing novel: This is the topic of the fantastic JTBD-driven sales book Demand Side Sales. It should be on everyone’s shelf.)

That’s how Ben Aldred, founder of ethical research CRM ConsentKit, thinks about it:

“Sales discovery calls feel just like doing user research, because you're trying to find out what the person's problem is, and then you're working out if you can actually solve it.”

So in the same way you’d start an interview asking for an overview, you can start out sales calls asking for overall context.

I generally start with a question to the effect of:

Before we get into [our product], I’m hoping to learn more about how this plays out at your [company/organization/team] and learn more about your [company/organization/team]. To start, I’m wondering if you might be able to give me an overview of your whole [project/process/work], and how [thing your product does] fits in.

It’s important to say something to the effect of “before we get into [our product]”, as they’ve come onto the call expecting to be pitched and expecting to learn about your product. Giving them a heads-up that you’ll be sharing more about your product later helps them relax into the question.

We generally avoid prompting in customer interviews, but in that vein of recognizing the expected social behavior in this situation, I encourage you to specifically prompt them on how whatever your product does fits into what they’re doing. It’s one more way to acknowledge that they’re here to learn about your product.

From there, dig into the specific parts of the process as well as their Buyer’s Journey:

What are they currently using (manual or another product)? Do they have a willingness to pay? => “Would you be able to walk me through your current process?” “Would you be able to share with me which vendor you’re currently using?”

Pain and frequency => “How often would you say your company is [doing this]?” “Could you tell me more about the overall priorities and goals this [project] feeds into?”

Where are they spending a lot of time or money? => If it hasn’t come across in their description of the process, “Where would you say you’re spending a lot of time or resources?”

Where are there frustrations? => “What’s leading you to consider doing this differently?”

When did they start thinking about buying something new to help with this, and why? How motivated are they to do something different? => “Can you tell me more about how interest in doing things differently came about?”

When interviewing a customer, you want to dig into the functional, social, and emotional aspects of each step of the process. But in a sales setting, they’re going to be justifiably guarded. I therefore focus my questions on functional and social elements (“who else is involved in this step of the process?” / “is there anyone else who will need to weigh in on which vendor you go with?”), but don’t ask any directly emotional questions. They might feel vulnerable enough being pitched to, and your goal is to put them at ease rather than heighten those feelings.

Using props (decks and demos)

Once you’ve gotten a solid understanding of what they’re trying to do, you can then begin to talk about what your company does and how you might be able to help.

For people who are less comfortable with talking and especially with sales, it’s often helpful to have a prop, such as a deck or a demo.

The key is to tailor it around the information they’ve told you in the first part of the call. A deck or a demo is a prop—a tool—but not an actor itself. Do not simply walk them through a standard slide deck or demo your entire product.

Ben Aldred again:

I have a list of questions that I go through. And it's all about trying to work out what their process is, because I'm trying to work out what parts of the product I can demo…

Like, are they trying to build their own research panel themselves? If they are, then I'll show them that part of the product. If they're not, because some people use external recruiters, I won't even show them that part of the product. There's no point.

The demo is a complement to the conversation, rather than the focus of the call itself.

If you have a 15-slide deck, skip to only the slides that are relevant to their JTBD and the conversation you’ve had. If you have a demo, skip to the features of your product that relate the most to the process they’ve told you about.

And when you show them a slide or a feature, spend more time asking what they think about it than talking yourself.

Slides and a demo are aides. When I’m giving a talk on stage, I try not to rely on slides very much. Perhaps I have something that can only be explained visually, like the fMRI images above. But most of the time, I think of the slides as being something that’s there if they get bored of looking at or listening to me. The slides are a fallback, rather than the focus.

(It’s still helpful to have the full slide deck and send it to them after, so they can circulate that internally. But you don’t need to make them sit through the whole thing.)

Always ask the reaching for the door question

You want to give the space to ask their own questions, and you also want to be able to get in the crucial reaching for the door question. But this looks a bit different than in an interview.

You might start an interview with a question to the effect of “Before we get started, do you have any questions for me?” Yet you want to move this to closer to the end in a sales call. “Now that I’ve gotten a better understanding of how this looks at your company and I’ve shared a bit about our product, I’m wondering what questions you might have for me.”

I encourage you to try to get to that question about 75% of the way through, as they might have several questions for you.

And after you’ve gotten through their questions, ask a version of the reaching for the door question. If you can, ask this no later than 90% of the way through:

“Well, thinking about your whole [process] we’ve talked about and how you’re looking [for a new solution/to make it more efficient/etc], is there anything else you think I should know?”

If the idea of asking “is there anything else you think I should know” in this context seems odd to you, you can rephrase:

“Well, thinking about your whole [process] we’ve talked about and how you’re looking [for a new solution/to make it more efficient/etc], is there anything else you hoped we would talk about?”

Sales without being salesy

There’s a lot of overlap between the skills used in customer research, sales, and negotiations. If you’ve wrapped your head around the skills in a customer research setting—even if you aren’t perfect or feel like you’ve mastered them—you can apply them elsewhere, and have sales conversations that feel more like conversations and are more comfortable for you and the prospect alike.

Ben Aldred again:

“If you learn the skills of user research, then you can get good at talking to your customers, but also talking to your prospects. So it's a transferable skill.”

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

On an entirely different note, I recently watched the new Netflix show The Residence, an amusing whodunit set in the White House. My favorite part—and the reason why I bring it up here—is that the detective investigating the case takes the “wait three seconds until it’s uncomfortable” tactic so well to to the point where it’s a running gag. She often waits quite a bit longer than three seconds, and it’s incredibly effective. If you’ve employed that tactic yourself, you’ll probably find it entertaining.

I hope you’ll allow me a very mild spoiler. My favorite part is when the detective is giving a Senator advice on how to question a witness via text message. I laughed out loud at this point, as it’s a bit how I feel when telling people to wait three seconds:

And on another entirely different note, I’ll be talking about talking to people at two conferences this fall:

Friendly.rb, September 10-11, Bucharest

MicroConf Europe, September 28-30, Istanbul

I’d love to see you there!

Have a great weekend,

Michele